Apollo, Dionysus, and the Return of Ritual

Catalogue essay for group exhibition at ZERUI Gallery

May 2022

Extract ---

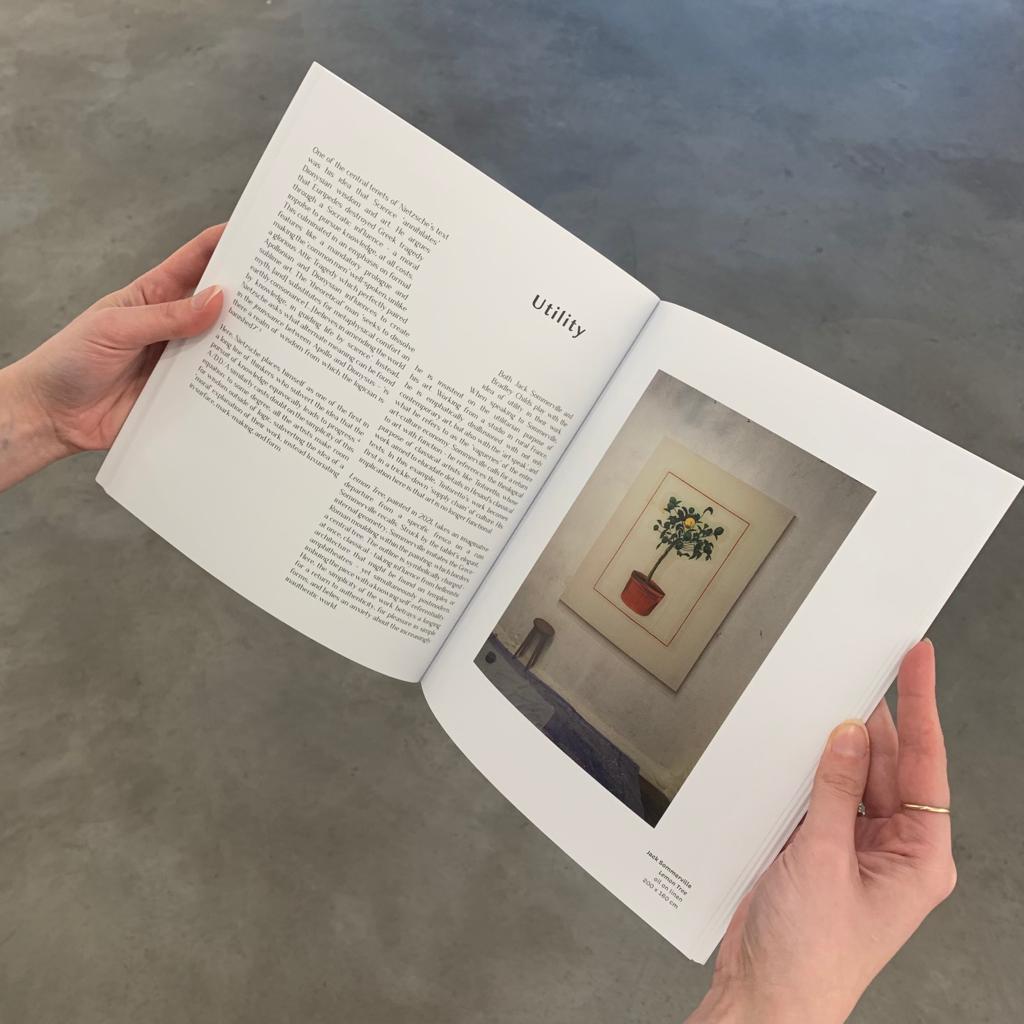

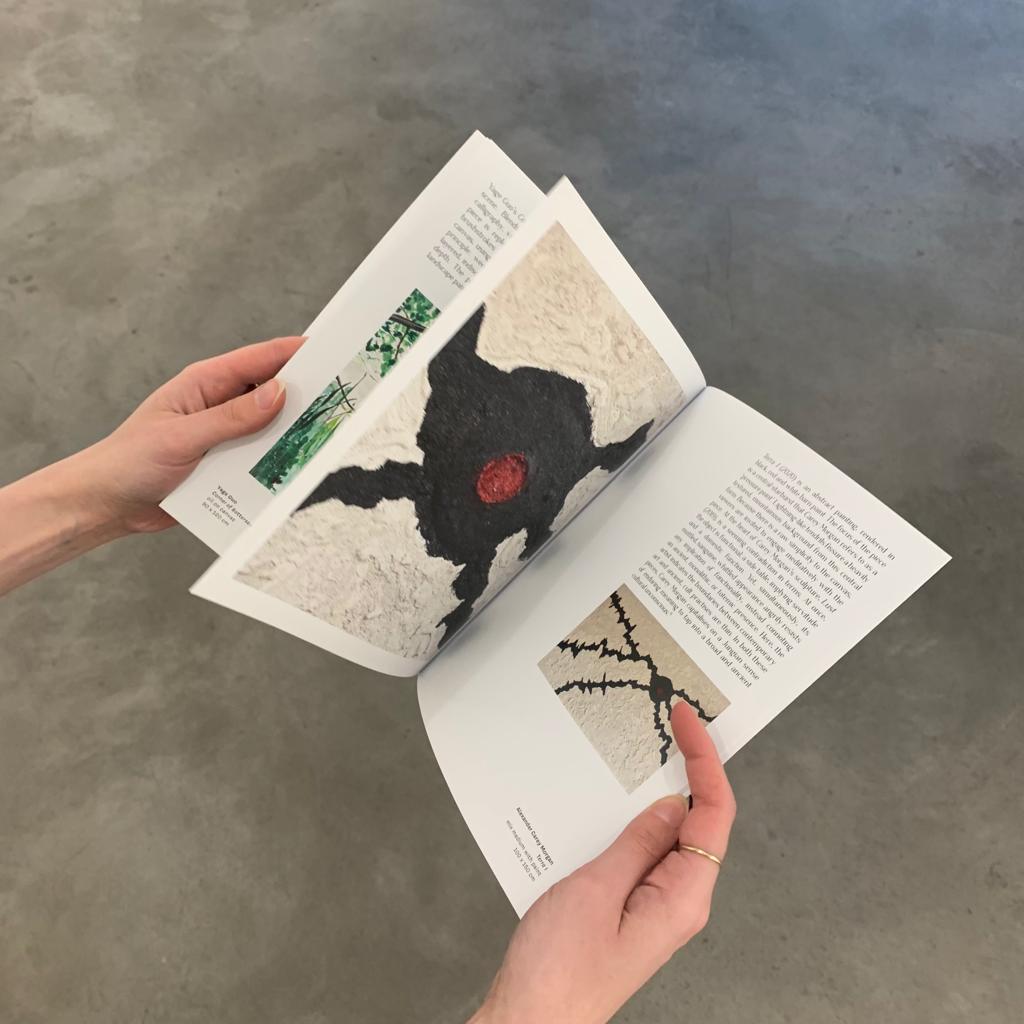

In 1872, Nietzsche wrote The Birth of Tragedy. In a long, rambling, and largely logically inconsistent way, he drew, sheepishly, on an nineteenth-century trend for extrapolating philosophy out of aesthetic categories. Here, between that of Dionysus, Ancient Greek God of Wine, and Apollo, God of Sun. To the Greeks, Apollo represented ‘measured limitation’, ‘the philosophical calmness of the sculptor-god’, whereas Dionysus was the ‘collapse’ of individuality; ‘drunkenness’, but also birth, becoming, and divine inspiration. In short, for Nietzsche, Dionysus signified chaos, Apollo signifies order, and to make the perfect Greek tragic play (or any art, in fact), you need a healthy dose of both.

Beyond this formal aesthetic distinction, Nietzsche also reflects on why the ‘cult’ of Dionysus had such a hold over Greek thought, influencing everything from their religious practises to their art and social structure. Using Nietzsche’s idiosyncratic, aesthetic philosophy, this text locates a nascent divinity in the works exhibited in A/D/D/A. The Ancient Greeks understood tragic theatre as a ritualistic act of commune with their Gods, and Nietzsche understood there to be an ‘intrinsic dependence of every art on Greek’. Does it follow, then, that this idea of ritual could still - consciously or unconsciously - factor into current artistic practises?

Origin

Greek Tragedy is widely understood to be an extension of ancient rites carried out in honour of Dionysus. Theatre wasn’t simply a performance, but inextricably bound up with worship, ritual, and cult practices. Here, Dionysus was both a character within tragedy, and the driving theme of the art. Leaning heavily on oral traditions, the tragedies undermine our modern idea of the author/artist, as they have no singular, original ‘author’.

In his 1960 book Dionysus, Myth and Cult, German historian and theologian Walter Otto reads a radical, mythic worldview into ancient Greek practises. He argues that in Greek Tragedy, the God Dionysus isn’t merely referred to, but is actually present within the Art. He argues this divine legacy exists still, today, and its ‘presence is attested to by the emotions of ecstasy and grace ’, even when ‘the arts seem to have a completely independent existence’. Here, like Greek plays, all creative practice ‘bears witness to the encounter of the supernatural’ - an originary, divine inspiration which drives creativity beyond the artist’s hand. Speaking to the artists in A/D/D/A, many of them consider the idea of Origin: most aren’t sure about where their paintings come from. Here, it is tempting to share Otto’s assertion that creative practises bear witness to an originary ‘divine’ inspiration.

Daniel Spivakov isn’t only uncertain about where his paintings come from - he’s also uncertain about where they go: the original painting intended for A/D/D/A was ‘overworked’ - returning ephemerally to the darkness from whence it came. Spivakov has two, primary methods of deferring origin in his work: the first is a dependence on source imagery in his Stitch series, and the second through utilising expressive, instinctive mark-making.

Love Want Issue 21/ The Virgin and Child by Giovanni Bellini (2021) is one of five in Spivakov’s Stitch series. Here, he splices together unrelated prints - one, a Renaissance painting, and the other, the cover of a contemporary art magazine. Here, Spivakov capitalises on a tradition of objet trouvé, allowing the viewer to hermeneutically complete the work by making connections between the two images. In doing this, he calls into question a contemporary hierarchy of images, gesturing - bleakly, perhaps - towards a contemporary aporia in which the dominant cultural mode is heterogeneity: large, gestural paint splatters atop the seam between the two images do little to unite the pictures. When talking about his work, he is quick to remove his own agency - the painting speaks for itself, creating a ‘closed-feedback loop’. Here, the power of the painting comes from assemblage, rather than the artist himself.

Spivakov’s second piece also defers a point of origin, but here, through instinctive mark-making. In Untitled (2021), a central, amorphous blue form is girdled by a thick, cream, ribbon. There is a discrepancy between an Apollonian order implied by this thick, encompassing line, and a Dionysian chaos in the busy, bruised, centre of the work. Here, he uses a painterly instinctiveness, creating a sense of wielding or harnessing a sourceless power. Spivakov absents himself, placing emphasis on the importance of process, instinctiveness, and materiality to dictate the outcome of his piece.

Where Spivakov’s Untitled suggests the artist channels an unknown origin, Jack Laver creates a further dissonance between art and artist by relying entirely on the alethic factors of chance and variation. He works by pouring a mixture of glue and inks onto stretched canvas, letting them run, bleed, and finally, set: like a scientific Petri dish, Laver returns to his works hours after the act of creation to see what has grown from these composite ingredients. The works can take days, even weeks to dry. While Laver starts with an initial concept - Bowed Angel, 2020 for example, uses the symbol of the angel as a starting point - and is also happy to interpret the final product - in Dying Day, 2020 he reads a stormy, apocalyptic landscape - what happens in the interim relies in part on the whims of his materials. Here the concept of the unknown and uncontrollable is fundamental.

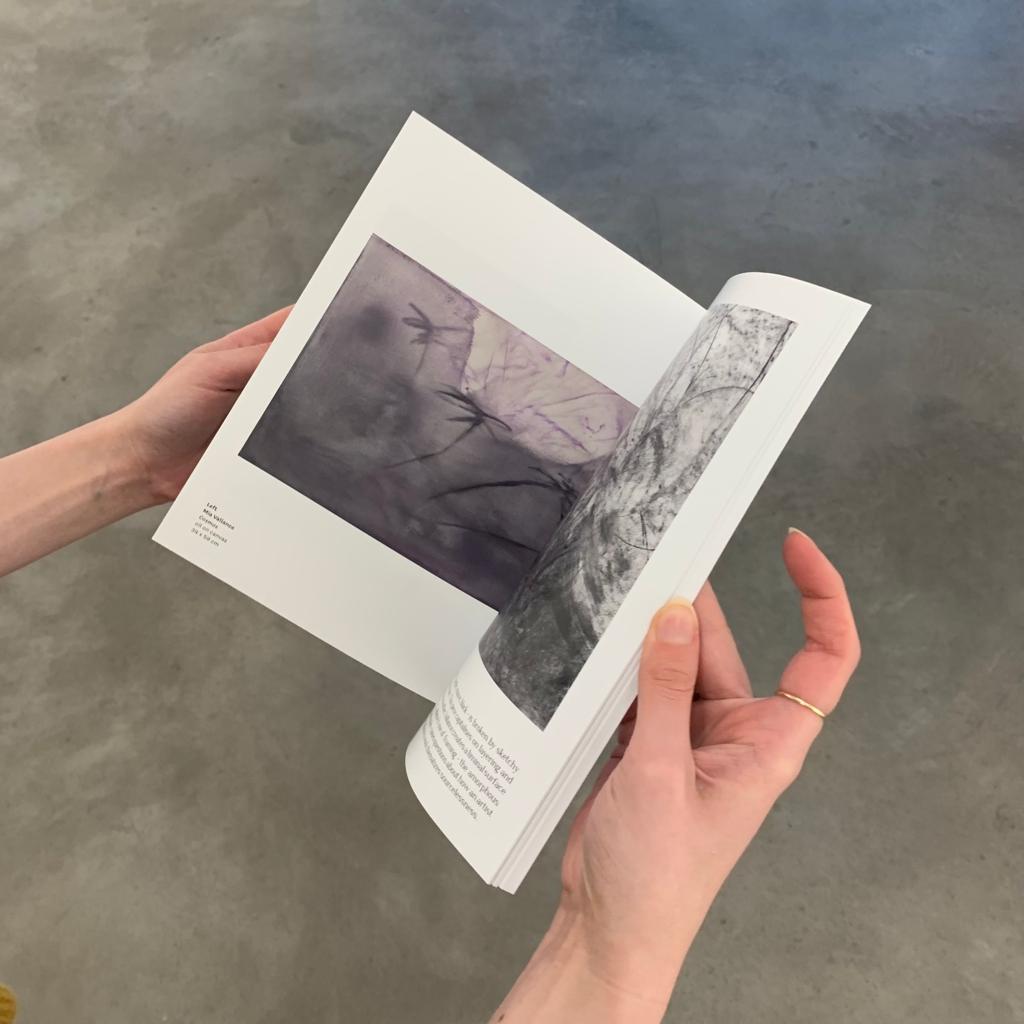

Central to Mia Vallance’s painting is the practice of attrition - carefully mixing and layering pigment and then dissolving it again using solvent until the ideal level of translucence is achieved. Described as ‘womb-like’, the Vallance’s two paintings capitalise on a lack of distinction between psychological and somatic space. They call into question not only origin, but presence - what are we looking at? Working in luminous palettes on rabbit-skin glue primed canvases, Ink Body (2021) depicts an oceanic green scene with a mysterious, blurred figure at it’s centre. The figure’s eyes are ominously marked with crosses; there is a small, inky mark to its lower left abdomen. Part cipher, part ghoul, the work hints at a troubled and unexplained presence. Untitled (2021) is similarly cryptic. The central colour palette - purple, mauve, black - is broken by sketchy ciphers, etched into the canvas like ink tendrils bleeding in water. This piece capitalises on layers and attrition for its potency: by playing these two techniques against one another, Vallance creates a liminal surface where the forces of building and destruction compete. Vallance’s use of framing - the amorphous canvas is (unexpectedly) neatly framed by a prim, white border - raises questions about how an artist martials an abstract landscape. Both in content and form, Mia Vallance’s work thematizes sourcelessness...

In situ

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

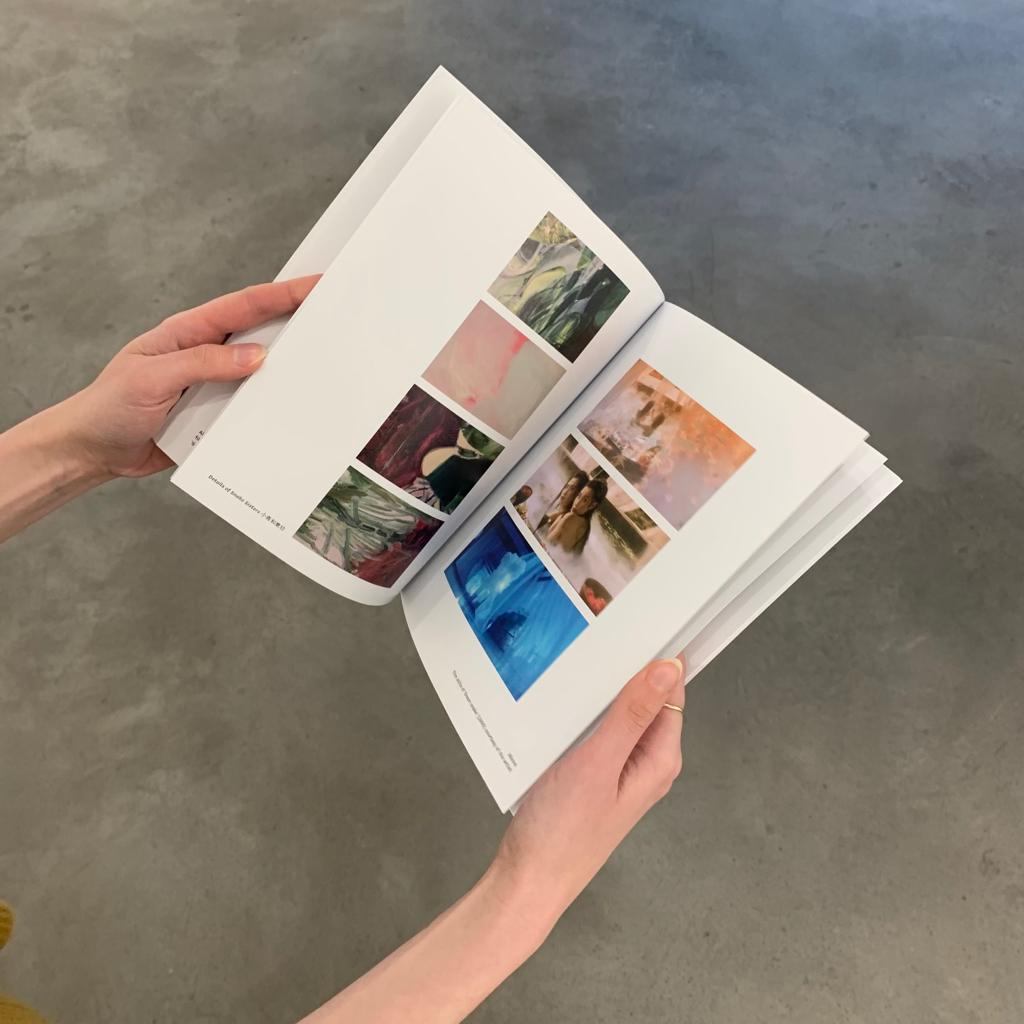

With works by Daniel Spivakov, Jack Laver, Mia Vallance, Jack Sommerville, Bradley Childs, Li Hei Di, Alexander Carey Morgan and Yage Guo.

44 pages, 23 x 20 cm.

Design by Cherryboy Magazine.

Published in 2022.

Apollo, Dionysus, and the Return of Ritual

Catalogue essay for group exhibition at ZERUI Gallery

May 2022

Extract ---

In 1872, Nietzsche wrote The Birth of Tragedy. In a long, rambling, and largely logically inconsistent way, he drew, sheepishly, on an nineteenth-century trend for extrapolating philosophy out of aesthetic categories. Here, between that of Dionysus, Ancient Greek God of Wine, and Apollo, God of Sun. To the Greeks, Apollo represented ‘measured limitation’, ‘the philosophical calmness of the sculptor-god’, whereas Dionysus was the ‘collapse’ of individuality; ‘drunkenness’, but also birth, becoming, and divine inspiration. In short, for Nietzsche, Dionysus signified chaos, Apollo signifies order, and to make the perfect Greek tragic play (or any art, in fact), you need a healthy dose of both.

Beyond this formal aesthetic distinction, Nietzsche also reflects on why the ‘cult’ of Dionysus had such a hold over Greek thought, influencing everything from their religious practises to their art and social structure. Using Nietzsche’s idiosyncratic, aesthetic philosophy, this text locates a nascent divinity in the works exhibited in A/D/D/A. The Ancient Greeks understood tragic theatre as a ritualistic act of commune with their Gods, and Nietzsche understood there to be an ‘intrinsic dependence of every art on Greek’. Does it follow, then, that this idea of ritual could still - consciously or unconsciously - factor into current artistic practises?

Origin

Greek Tragedy is widely understood to be an extension of ancient rites carried out in honour of Dionysus. Theatre wasn’t simply a performance, but inextricably bound up with worship, ritual, and cult practices. Here, Dionysus was both a character within tragedy, and the driving theme of the art. Leaning heavily on oral traditions, the tragedies undermine our modern idea of the author/artist, as they have no singular, original ‘author’.

In his 1960 book Dionysus, Myth and Cult, German historian and theologian Walter Otto reads a radical, mythic worldview into ancient Greek practises. He argues that in Greek Tragedy, the God Dionysus isn’t merely referred to, but is actually present within the Art. He argues this divine legacy exists still, today, and its ‘presence is attested to by the emotions of ecstasy and grace ’, even when ‘the arts seem to have a completely independent existence’. Here, like Greek plays, all creative practice ‘bears witness to the encounter of the supernatural’ - an originary, divine inspiration which drives creativity beyond the artist’s hand. Speaking to the artists in A/D/D/A, many of them consider the idea of Origin: most aren’t sure about where their paintings come from. Here, it is tempting to share Otto’s assertion that creative practises bear witness to an originary ‘divine’ inspiration.

Daniel Spivakov isn’t only uncertain about where his paintings come from - he’s also uncertain about where they go: the original painting intended for A/D/D/A was ‘overworked’ - returning ephemerally to the darkness from whence it came. Spivakov has two, primary methods of deferring origin in his work: the first is a dependence on source imagery in his Stitch series, and the second through utilising expressive, instinctive mark-making.

Love Want Issue 21/ The Virgin and Child by Giovanni Bellini (2021) is one of five in Spivakov’s Stitch series. Here, he splices together unrelated prints - one, a Renaissance painting, and the other, the cover of a contemporary art magazine. Here, Spivakov capitalises on a tradition of objet trouvé, allowing the viewer to hermeneutically complete the work by making connections between the two images. In doing this, he calls into question a contemporary hierarchy of images, gesturing - bleakly, perhaps - towards a contemporary aporia in which the dominant cultural mode is heterogeneity: large, gestural paint splatters atop the seam between the two images do little to unite the pictures. When talking about his work, he is quick to remove his own agency - the painting speaks for itself, creating a ‘closed-feedback loop’. Here, the power of the painting comes from assemblage, rather than the artist himself.

Spivakov’s second piece also defers a point of origin, but here, through instinctive mark-making. In Untitled (2021), a central, amorphous blue form is girdled by a thick, cream, ribbon. There is a discrepancy between an Apollonian order implied by this thick, encompassing line, and a Dionysian chaos in the busy, bruised, centre of the work. Here, he uses a painterly instinctiveness, creating a sense of wielding or harnessing a sourceless power. Spivakov absents himself, placing emphasis on the importance of process, instinctiveness, and materiality to dictate the outcome of his piece.

Where Spivakov’s Untitled suggests the artist channels an unknown origin, Jack Laver creates a further dissonance between art and artist by relying entirely on the alethic factors of chance and variation. He works by pouring a mixture of glue and inks onto stretched canvas, letting them run, bleed, and finally, set: like a scientific Petri dish, Laver returns to his works hours after the act of creation to see what has grown from these composite ingredients. The works can take days, even weeks to dry. While Laver starts with an initial concept - Bowed Angel, 2020 for example, uses the symbol of the angel as a starting point - and is also happy to interpret the final product - in Dying Day, 2020 he reads a stormy, apocalyptic landscape - what happens in the interim relies in part on the whims of his materials. Here the concept of the unknown and uncontrollable is fundamental.

Central to Mia Vallance’s painting is the practice of attrition - carefully mixing and layering pigment and then dissolving it again using solvent until the ideal level of translucence is achieved. Described as ‘womb-like’, the Vallance’s two paintings capitalise on a lack of distinction between psychological and somatic space. They call into question not only origin, but presence - what are we looking at? Working in luminous palettes on rabbit-skin glue primed canvases, Ink Body (2021) depicts an oceanic green scene with a mysterious, blurred figure at it’s centre. The figure’s eyes are ominously marked with crosses; there is a small, inky mark to its lower left abdomen. Part cipher, part ghoul, the work hints at a troubled and unexplained presence. Untitled (2021) is similarly cryptic. The central colour palette - purple, mauve, black - is broken by sketchy ciphers, etched into the canvas like ink tendrils bleeding in water. This piece capitalises on layers and attrition for its potency: by playing these two techniques against one another, Vallance creates a liminal surface where the forces of building and destruction compete. Vallance’s use of framing - the amorphous canvas is (unexpectedly) neatly framed by a prim, white border - raises questions about how an artist martials an abstract landscape. Both in content and form, Mia Vallance’s work thematizes sourcelessness...

In situ

Catalogue essay for group exhibition at ZERUI Gallery

May 2022

Extract ---

In 1872, Nietzsche wrote The Birth of Tragedy. In a long, rambling, and largely logically inconsistent way, he drew, sheepishly, on an nineteenth-century trend for extrapolating philosophy out of aesthetic categories. Here, between that of Dionysus, Ancient Greek God of Wine, and Apollo, God of Sun. To the Greeks, Apollo represented ‘measured limitation’, ‘the philosophical calmness of the sculptor-god’, whereas Dionysus was the ‘collapse’ of individuality; ‘drunkenness’, but also birth, becoming, and divine inspiration. In short, for Nietzsche, Dionysus signified chaos, Apollo signifies order, and to make the perfect Greek tragic play (or any art, in fact), you need a healthy dose of both.

Beyond this formal aesthetic distinction, Nietzsche also reflects on why the ‘cult’ of Dionysus had such a hold over Greek thought, influencing everything from their religious practises to their art and social structure. Using Nietzsche’s idiosyncratic, aesthetic philosophy, this text locates a nascent divinity in the works exhibited in A/D/D/A. The Ancient Greeks understood tragic theatre as a ritualistic act of commune with their Gods, and Nietzsche understood there to be an ‘intrinsic dependence of every art on Greek’. Does it follow, then, that this idea of ritual could still - consciously or unconsciously - factor into current artistic practises?

Origin

Greek Tragedy is widely understood to be an extension of ancient rites carried out in honour of Dionysus. Theatre wasn’t simply a performance, but inextricably bound up with worship, ritual, and cult practices. Here, Dionysus was both a character within tragedy, and the driving theme of the art. Leaning heavily on oral traditions, the tragedies undermine our modern idea of the author/artist, as they have no singular, original ‘author’.

In his 1960 book Dionysus, Myth and Cult, German historian and theologian Walter Otto reads a radical, mythic worldview into ancient Greek practises. He argues that in Greek Tragedy, the God Dionysus isn’t merely referred to, but is actually present within the Art. He argues this divine legacy exists still, today, and its ‘presence is attested to by the emotions of ecstasy and grace ’, even when ‘the arts seem to have a completely independent existence’. Here, like Greek plays, all creative practice ‘bears witness to the encounter of the supernatural’ - an originary, divine inspiration which drives creativity beyond the artist’s hand. Speaking to the artists in A/D/D/A, many of them consider the idea of Origin: most aren’t sure about where their paintings come from. Here, it is tempting to share Otto’s assertion that creative practises bear witness to an originary ‘divine’ inspiration.

Daniel Spivakov isn’t only uncertain about where his paintings come from - he’s also uncertain about where they go: the original painting intended for A/D/D/A was ‘overworked’ - returning ephemerally to the darkness from whence it came. Spivakov has two, primary methods of deferring origin in his work: the first is a dependence on source imagery in his Stitch series, and the second through utilising expressive, instinctive mark-making.

Love Want Issue 21/ The Virgin and Child by Giovanni Bellini (2021) is one of five in Spivakov’s Stitch series. Here, he splices together unrelated prints - one, a Renaissance painting, and the other, the cover of a contemporary art magazine. Here, Spivakov capitalises on a tradition of objet trouvé, allowing the viewer to hermeneutically complete the work by making connections between the two images. In doing this, he calls into question a contemporary hierarchy of images, gesturing - bleakly, perhaps - towards a contemporary aporia in which the dominant cultural mode is heterogeneity: large, gestural paint splatters atop the seam between the two images do little to unite the pictures. When talking about his work, he is quick to remove his own agency - the painting speaks for itself, creating a ‘closed-feedback loop’. Here, the power of the painting comes from assemblage, rather than the artist himself.

Spivakov’s second piece also defers a point of origin, but here, through instinctive mark-making. In Untitled (2021), a central, amorphous blue form is girdled by a thick, cream, ribbon. There is a discrepancy between an Apollonian order implied by this thick, encompassing line, and a Dionysian chaos in the busy, bruised, centre of the work. Here, he uses a painterly instinctiveness, creating a sense of wielding or harnessing a sourceless power. Spivakov absents himself, placing emphasis on the importance of process, instinctiveness, and materiality to dictate the outcome of his piece.

Where Spivakov’s Untitled suggests the artist channels an unknown origin, Jack Laver creates a further dissonance between art and artist by relying entirely on the alethic factors of chance and variation. He works by pouring a mixture of glue and inks onto stretched canvas, letting them run, bleed, and finally, set: like a scientific Petri dish, Laver returns to his works hours after the act of creation to see what has grown from these composite ingredients. The works can take days, even weeks to dry. While Laver starts with an initial concept - Bowed Angel, 2020 for example, uses the symbol of the angel as a starting point - and is also happy to interpret the final product - in Dying Day, 2020 he reads a stormy, apocalyptic landscape - what happens in the interim relies in part on the whims of his materials. Here the concept of the unknown and uncontrollable is fundamental.

Central to Mia Vallance’s painting is the practice of attrition - carefully mixing and layering pigment and then dissolving it again using solvent until the ideal level of translucence is achieved. Described as ‘womb-like’, the Vallance’s two paintings capitalise on a lack of distinction between psychological and somatic space. They call into question not only origin, but presence - what are we looking at? Working in luminous palettes on rabbit-skin glue primed canvases, Ink Body (2021) depicts an oceanic green scene with a mysterious, blurred figure at it’s centre. The figure’s eyes are ominously marked with crosses; there is a small, inky mark to its lower left abdomen. Part cipher, part ghoul, the work hints at a troubled and unexplained presence. Untitled (2021) is similarly cryptic. The central colour palette - purple, mauve, black - is broken by sketchy ciphers, etched into the canvas like ink tendrils bleeding in water. This piece capitalises on layers and attrition for its potency: by playing these two techniques against one another, Vallance creates a liminal surface where the forces of building and destruction compete. Vallance’s use of framing - the amorphous canvas is (unexpectedly) neatly framed by a prim, white border - raises questions about how an artist martials an abstract landscape. Both in content and form, Mia Vallance’s work thematizes sourcelessness...

In situ

With works by Daniel Spivakov, Jack Laver, Mia Vallance, Jack Sommerville, Bradley Childs, Li Hei Di, Alexander Carey Morgan and Yage Guo.

44 pages, 23 x 20 cm.

Design by Cherryboy Magazine.

Published in 2022.